I spent an incredibly busy Spring recording with Suggested Friends, then going to the AAG in New Orleans, then going on tour to Germany with Chorusgirl, then going to the CIG in Maynooth. I often compare musician life with academia life because it relies so much on patronage, casualisation, and the erosion of expectations around earning any money or having any security - or any time off. But over the course of the last few shows with both of my bands I think the main point of departure really is the complete expectation of no reimbursement with regarding to academic conferencing, and how many working class people that must exclude (NB. I am culturally and materially middle class, though members of my family have working class origins). With touring you can plan it out and hope for the best that you at least won't lose a big chunk of money. For PhD students on limited stipends and research training grants, it's just a given that doing the things that seem vital to entering academia will cost you a lot of money. Just another contradiction of academia I suppose - people love theorising about money and researching the way people use it but they don't really talk about how much they have or where it's coming from. Institutions foster this through making expenses claims systems infuriatingly labyrinthine, and through the acceptability that payment for literal labour might take months and months to process. I'm still waiting to be paid for some marking I did in December! Anyway, venting aside, the purpose of this post was to upload some of my AAG and CIG papers. Since the CIG paper pretty much ended up being a fine-tuned version of the AAG one, I'll stick to that. The session was about 'Compensatory Homemaking' so I've referred to 'compensatory' labour to resonate with that. It sounds very bullet-pointy because that's the way I have to write papers to stop my eyes being glued to the page, and I've chopped some stuff out to make this post more digestible!:

A Tale of Two Boroughs: Social Reproduction, Capital, and Homemaking in Hackney’s Rental Market

‘Generational inequality’ is increasingly seen as having bifurcated the political and economic conditions of the UK population. From Brexit to declines in real wages, a central feature of political commentary relies on the construction of beleaguered millennials bearing the brunt of baby boomer wealth and its accompanying fiscal conservatism e.g. new 10k inheritance leveler/pensioner tax.

Within this discourse, one repercussion of long-term renting and the scarcity of past routes to stable employment is the inability to ‘reproduce’ a family; pathways to the nuclear family fantasy have been obstructed, and often the destination has changed. My research deals with the material experience and narrative of economic insecurity as a factor in the reconfiguration of ‘normative’ relatedness.

We can embrace the factual economic foundations of this narrative of millennial economic loss, and also query its unanimity. What does a narrative of generational disparity actually do for our understanding of class?

Themes emerging from my fieldwork with 18-35 year-old tenants in Hackney illuminate the ways that ‘lost’ capital is compensated for through the pooling of resources among private renters and the intimate labour expended in the reproduction of capital. My research has also revealed the ways that this capital reproduction impinges on the everyday social reproduction of those partially or fully excluded from private rental markets.

Outline of paper contents:

I. Intimate labour in UK austerity context

II. Methodology

III. Theory and Empirics

IV. Summary of Themes

I. Intimate and Compensatory Labour in UK Austerity Context

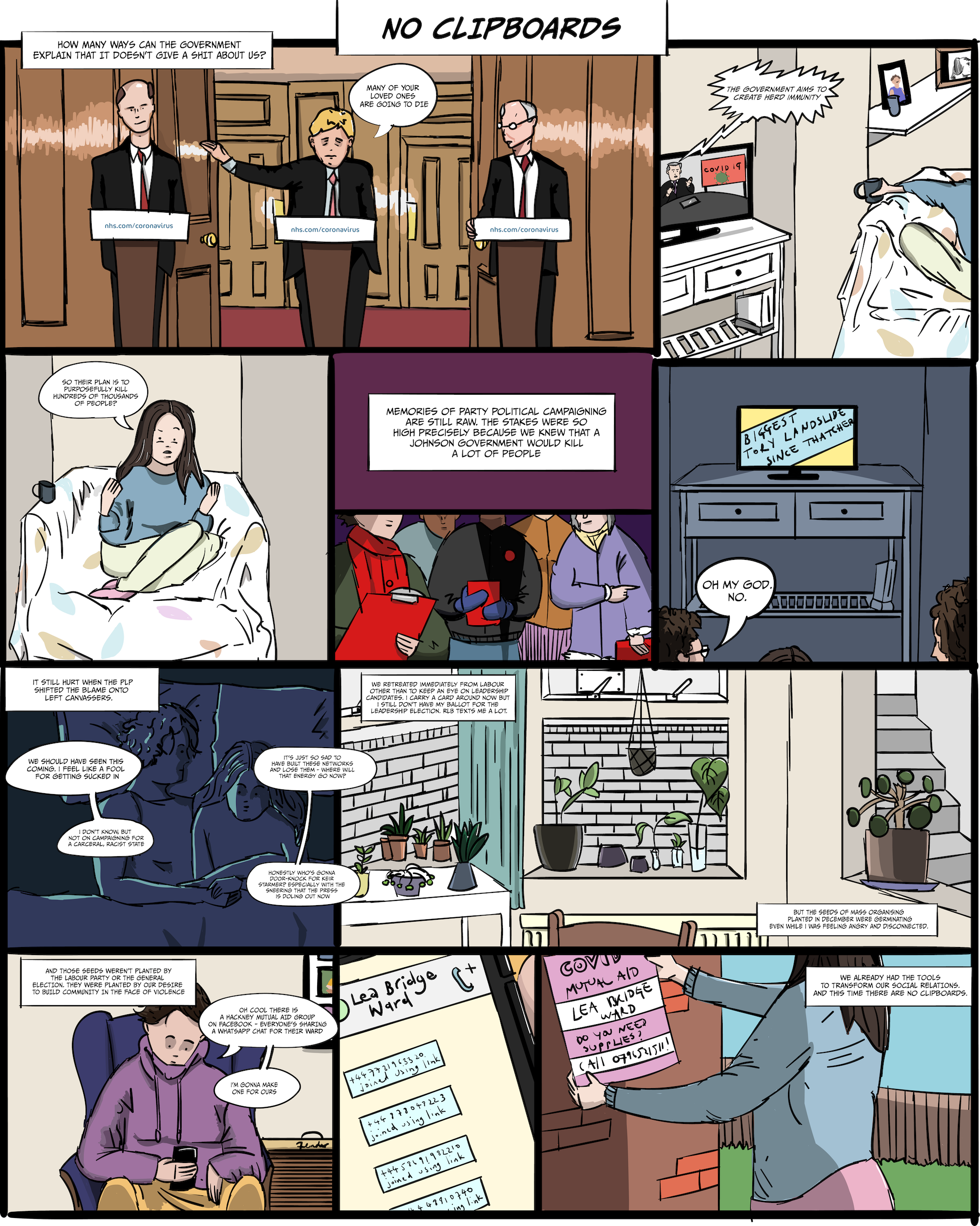

We can see this unfold empirically in the effects of the UK’s unrelenting housing ‘crisis’, an effect of over a decade of austerity and the privatization of public wealth. The impetus to expend intimate labour to conserve and add value to property assets and markets is inscribed in policy. One example: ‘under-occupancy’ charges for social housing tenants introduced in the 2012 Reform Act force families to share less space or relocate, thereby freeing up social homes for private sale.

Intimate labour is demanded indirectly, too, through the rising costs of living: financial resources are hastily pooled in new romantic partnerships through premature co-habitation in a private rental market that all but incentivises the merging of lives. These types of negotiation are at the foreground of the social reproduction of everyday life, but they are also deeply embedded in the work of ‘compensatory homemaking’ that goes into the reproduction of societal relations. For example, a couple will pool private rental resources only when each person has comparable financial security, whether this is in the form of a salaried income or financial safety nets through inherited wealth or familial support. This is literally encouraged by the deregulation of housing, e.g. through letting agents requiring guarantors. Forming partnerships and friendships with people that are invested in and/or have access to similar trajectories is a common theme.

The impact that market exclusivity has on ‘millennials’ from poorer backgrounds extends the imperative to perform compensatory labour to other forms of space: urban, virtual, and imagined. As salaried or financially cushioned private tenants configure and consolidate networks of relatedness for ‘house sharing’, young people ‘stuck’ in their family homes turn to other forms of space to meet, nurture ties, escape pressures, and create identities. In this way, millennial ‘homemaking’ that is based around shared resources and shared interests is both a result of the imposition of market capital accumulation and often a preserve of wealthier young renters. For this reason the discourse around ‘renters rights’ is often framed in terms of ‘value-for-money’.

II. Situating this in Hackney

Hackney is a ‘super-diverse’ borough in London and is also statistically young. There is a proportionally very high level of social housing in Hackney (44%), but the private rental market is also ‘booming’. House prices have spiraled; the average private renter in the area spends almost 75% of their income on rent, making it the most proportionally expensive place to rent in London.

My fieldwork has shown me that the distinction between private and social renters is needless, given that much of social housing is being privatized. Hackney is full of young people from different backgrounds who grew up in the area but can’t afford to live ‘independently’. Moreover, the frequency with which private sector renters move house makes it easier to increase rents in a given area, further locking social tenants out of markets. This situation is partly a result of assured fixed term tenancies that function in the interest of landlords and increase private rental insecurity.

III. Theory and Empirics (5 mins)

My fieldwork as much as my reading has informed the ways I’ve started to see and understand social reproduction as something that rooted in the intimate, affective, and precarious labour of managing and reproducing relationships. With this in mind I will be elaborating on some of my theoretical framework through empirical examples from my research.

Some background on the theoretical foundations that led me to my project: for me, intimacy is rooted in affective rather than physical relatedness. This disentangles essentialising discourses around the ways that families and wider relationships are constituted (Pratt & Rosner, 2012). Intimacy need not be thought of as physical and neither should reproduction. Social reproduction is a useful idea in this capacity because it helps us to deconstruct where life ‘starts’. Deconstructing the association between intimacy and physicality, and the fetishisation of reproduction as genetic paternity, is also a key part of challenging rape culture. This allows us to shift focus to a broader assemblage of activities constituting intimate life.

In order to look at the ways that intimacy is ‘done’ amidst economic insecurity, we have to acknowledge the patriarchal ideologies that are embedded in mainstream economic policy-making. Historically, essentialism has abounded in influential discourses around the ways economies affect family formation e.g. demographic transition theory relies on ethnocentric concepts like age at marriage and reproductive ‘behaviour’ without questioning the universality of categories and subjects. Fusing ‘economic growth’ to declining fertility is ideologically useful for a system premised on blaming the poor for their own poverty. You can see these Malthusian tropes in Tory policy, e.g. benefit sanctions for multiple kids.

I use the notion of ‘precarity’ to identify points of continuity across these scales, from state policy to everyday life. Precarity is a political, economic, and affective phenomenon, so it’s useful for looking at the way the state’s actions transmit across different levels of life. ‘Precarity’ is used in my work as something that is ‘felt’ affectively between and among people, that is imposed through policy, and as a broad theme framing contemporary understandings of generational inequality under UK austerity policies (Berlant, 2007, 2011). In this way, precarity acts as a useful bridge between thinking about social reproduction as labour and thinking about it as the reproduction of social hierarchies. The idea of social reproduction being in ‘crisis’ can relate to a crisis in caring labour, but I think it can also relate to a crisis in ‘social mobility’ comprised of economic obstacles to the reproduction of particular relationship models. Examining the way precarity manifests in the subtler moments of the everyday can help with integrating the social reproduction of class into the social reproduction of daily life, and how we impact each other. In short, social reproduction is bound up with intimacy and precarity across scales. Here I’m going to let an example from my fieldwork elaborate:

DT: Insecure Private Renting and Identity

DT is 30 and lives with her partner and their two-year-old child. DT explained to me the difficulties of sharing so little space with her partner and child:

We all just cram in. We have taken the side off C’s cot – she has never spent a night in it, but, sometimes I sleep diagonal in the cot, with my legs on the bed […] Have you seen the film Away We Go? With Maggie Gyllenhall? Her character is this hippie mum who does extended breastfeeding and her partner is a stay-at-home Dad and they have this family bed. […] which is basically just a whole room that’s a bed and I’m like… actually that’s an amazing idea.

The expense of private renting has required DT to settle for a space that is structurally unsafe and legally insecure. But this is something that is rationalised through her own class imagination. She negotiates precarity through intimate refashioning: the bed a site on which to inscribe her identity and not just sleep. The temporariness of her situation is also something she refers to – how she dreams of something different, partly because change is not completely intangible. She compensates for her lack of stability through reconciling temporariness to her situation.

We talk about what we would do if we had money. Would we get on? Because we have this underdog status. And like, you know we’ve got this shared enemy of the landlords, and the housing market, and if we were able to sort of comfortably be part of that environment, and we were able to afford a nice place, or even just get on the housing ladder, would mean – what would we talk about? What would we complain about? […] Maybe me and B will split up as soon as we leave London. That’d be sad for C.

DT's precarity is part-facilitated by market participation but also because labour has been done to reconcile that specific mode of consumption to her intimate life. In this example, the social reproduction of everyday life is interrupted by precarious materialities, but this precarity in itself becomes a vehicle for the social reproduction of an underdog status that is paradoxically both exploited and relatively class-privileged.

Tithi Bhattacharya’s suggestion that social reproduction be understood in terms of both exploitation and oppression might point to the use of power and capital as interchangeable concepts. The inextricable connections between power and capital are certainly palpable in the context of London’s housing crisis, at the most intimate levels of life; in the closure of domestic violence refuges, not only does the government also act as abusive partner, consigning women to literal murder by their partners, but the power that men have over women is literally given a currency in the form of shelter. But this relationship between power and capital can also operate more subtly: for example, capital might mean an exchangeable commodity in the form of classed knowledge for housing access. As in the example of DT, this type of knowledge might comprise a fetishisation of precarity.

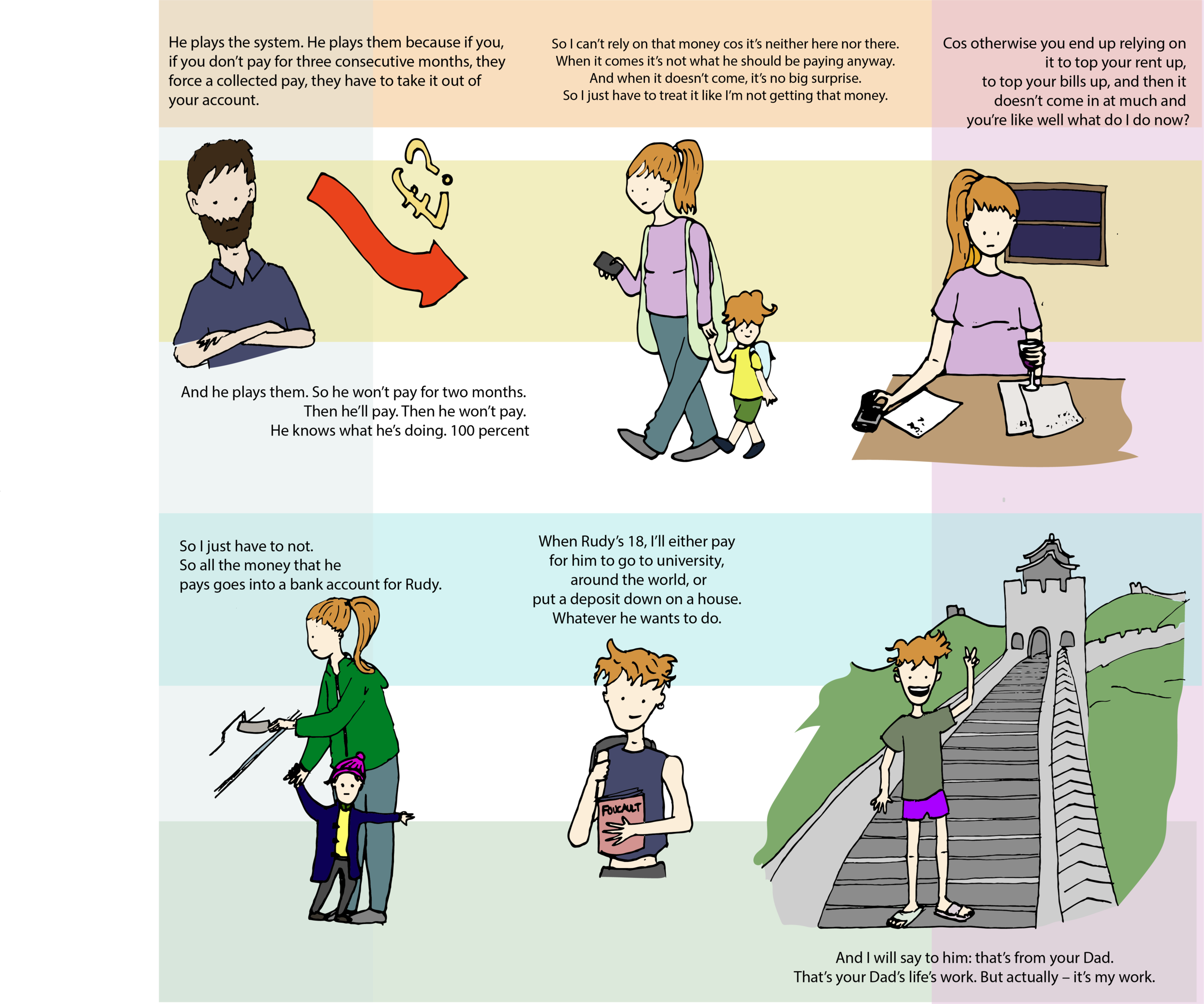

My research has become in many ways a political economy of intimacy and attachment, beginning from an understanding of love as labour, and of labour as a ‘unique commodity’ that can be bought and sold. In this regard, my work views intimacy and relatedness as not simply disrupted by the market relations of contemporary capitalism, but as a vehicle through which capital is exchanged, accumulated, stored, or lost. As SR’s and OP’s narratives show, families and friendships are rich sites of imagination for reconfiguring and compensating for a lack of space, security, and wealth. However, different types of bargaining take place outside of the realm of the private market, where a process of refashioning must be done for basic forms of housing access rather than personal legitimation:

KC: Trading in Feelings, Compensating with Consumer Space

KC is 24 and lives on a council estate. He ended up living in Hackney as a young teenager because his family was able to do a ‘council house swap’ with another family who wanted to live elsewhere in London. This happens often because families ‘under-occupying’ socially rented homes are forced to find smaller properties.

We did a house swap – we used to live in Finsbury Park, on the Hackney side of it. And it was a two-bedroom maisonette and I was like kind of sharing with my little sister, […] She was always in my face, always in my space. And at 14 we were getting family counselling, and I think that kind of gave weight to our – you know they have like a points system? To exchange houses and things like that […] So like the therapy thing actually worked out to help us. We found this couple that, her mum just died, so they had extra rooms and they needed – they were getting pushed out of the house.

Within this we see a very clear exchange of intimate hardship for security and space. Private market exclusion rendered his household a tradeable commodity in itself – one that is useful to increasing values and rents in a gentrifying area. KC's ability to trade in feelings – to swap his sibling stress with bereavement – allowed his family to negotiate the space to exist in the area.

Last night was just weird, it was the first time. The guy, I dunno who he was. I was literally here, reading my papers. This was about midnight. And he was like ‘I’m gonna go upstairs, and when I come back you need to be gone’ […] He was like ‘are you homeless? Do you need somewhere to stay or something? Are you dumb? Get out, you’re a tramp’[…]All my friends still live with their families. My house specifically, cos my parents are so nosy, they’ll like smell weed on us. Or even like, just chilling in my house, it’s not really that freeing, because the walls are so thin, so you can’t really like just speak your minds. It’s like, don’t swear, got to speak in hushed tones, so it’s not a good place to try and relax. It’s the same for my next door neighbours. Yeah the trick is to find a warm place, ideally with sofas. And where you’re not forced to spend eighteen pounds.

KC compensates for his lack of independent home space by attempting to socialise in public spaces, but is repeatedly obstructed from doing so by the obligation to pay to exist in cafes and restaurants. He later describes how he was asked to stop coming to a café because he ‘only bought coffees’. While his ability to ‘home-make’ is pushed outside of the physical space of his house, its lack of market usage carries stigma. Through this type of exclusion, we see how the market subjects KC’s relationships to a process of valuation, and designates them as more valuable outside of the area he lives in.

JT: State Interventions in Social Reproduction, Compensating through Fiction

They put us in <South London>. They said if we wanted to stay in Hackney they’d have to split us. We didn’t have no friends, nowhere to go, it was just –yep. For us it was like a no-man’s land. So they said, oh yeah you can still go to school in Hackney, but you’ll have to get driven. So at the time we had to get a taxi, which was awkward because our friends didn’t know so they were like ‘oh why are you coming in in a taxi with this man you don’t know?’ and so for a little while the cab driver had to pose as our dad, because we were just embarrassed, and the school didn’t want too many questions.

In this there is an imperative to perform familial normativity, and to ‘home-make’ while literally in transit between JT’s displacement-home and her actual home and community in Hackney. This fictional compensation JT makes for her lack of relationship to the taxi driver and the responsibility she feels to maintain a visage of normalcy operates as a labour of legitimation for her continued existence in Hackney.

Themes

Market inclusion/market exclusion changes the way we perceive affordability, and what we are compensating for: am I compensating the state and consumers for my existence, or am I compensating for the entitlements I had once envisioned for myself?

Privatization of social housing bars poorer tenants from being considered consumers but makes their living situations more insecure and more policed: if they cannot pay they become the product

Discourse of ‘millennial precarity’ propels the ideologically useful separation of social/private tenant; we need to separate payment from entitlement.

Focusing on intimacy and reproduction of relationships allows us to locate points of continuity and solidarity between seemingly disparate lives; it’s not like market participants don’t feel insecurity, they just get more airtime.

References:

Berlant, L., 2007. Nearly Utopian, Nearly Normal: Post-Fordist Affect in La Promesse and Rosetta.Public Culture 19:2, 273-301. doi 10.1215/08992363-2006-036

Berlant, L., 2011. Cruel Optimism. Durham: Duke University Press

Bhattacharya, T., 2017. Social Reproduction Theory: Remapping Class, Recentering Oppression. London: Pluto Press

Pratt, G., Rosner, V., 2013. The Global and the Intimate: Feminism in Our Time. New York: Columbia University Press

**********

There you have it folks.

Peace!